When Edgar Allan Poe taught how to write “The Raven”

“I say to myself, in the first place, “Of the innumerable effects, or impressions, of which the heart, the intellect, or (more generally) the soul is susceptible, what one shall I, on the present occasion, select?” - Edgar Allan Poe

When Jorge Luís Borges says that his life would be over if his accident left him incapable of writing literature, there's a feeling of devotion to art that finds ressonance in other great artists. His vision can be romantic to others, among those is the writer Edgar Allan Poe. In 1946 the essay “Philosophy of composition” was published in the Graham's Magazine, on it he not only questions this “inspiration” but also explain how his creative method can work in such a calculated manner.

“Most writers — poets in especial — prefer having it understood that they compose by a species of fine frenzy — an ecstatic intuition — and would positively shudder at letting the public take a peep behind the scenes, at the elaborate and vacillating crudities of thought...”

He goes right to the point when talking about his writing: “the work proceeded, step by step, to its completion with the precision and rigid consequence of a mathematical problem”. It may be frigid and rough but he uses his famous poem – The Raven – to explain these uncommon positions. Along the essay he lists the steps taken to compose. One of them relates to the length of the poem:

“...the extent of a poem may be made to bear mathematical relation to its merit (…) to the degree of the true poetical effect which it is capable of inducing; for it is clear that the brevity must be in direct ratio of the intensity of the intended effect: — this, with one proviso — that a certain degree of duration is absolutely requisite for the production of any effect at all. “

He wanted a poem to be aprecciated by everyone, that's why he believedthat the intensity of the poem should be in the reach of the popular reader but not too low to be dismissed by the critics. This decision influenced also the extension of the poem that had 100 verses as objective. The final version have 108. However, he defends that the way to convey this intensity passes invariably through the Beauty:

“Now I designate Beauty as the province of the poem, merely because it is an obvious rule of Art that effects should be made to spring from direct causes — that objects should be attained through means best adapted for their attainment — no one as yet having been weak enough to deny that the peculiar elevation alluded to, is most readily attained in the poem.”

The Beauty presents itself in the poem through the dead lover and form this come the extreme melancholic tone. Poe sees the melancholy as “the most legitimate of all the poetical tones”. And why a raven? When he chose the word “nevermore” as a conductor of the poem he needed to create a way to insert it's repetition. It could be a parrot, but the raven was more adequate to the melacholic tone and fit his desire for repetition because he knew it had to be an animal able to speak in some manner, since a person wouldn't work in the poem if she was to say the same thing over and over again.

In this poetic work, as in his prose there's a element of strangeness that generates the melancholy and the fear. Despite everything laying in the border between fantasy and improbable reality, in this essay he explains that his intention is to never go beyond what is really possible. In the poem he imagines the student dialoguing with the raven that can only say “nevermore”, but the disposition of the student in hearing the answers that he can foresee as all the same and asking questions accordingly come from, according to Poe, a “thirsty for selftorture” and “in part due to superstition”. Yet, he understands that this calculated approach can undermine the artistic quality of the poem:

“But in subjects so handled, however skilfully, or with however vivid an array of incident, there is always a certain hardness or nakedness, which repels the artistical eye. Two things are invariably required — first, some amount of complexity, or more properly, adaptation; and, secondly, some amount of suggestiveness — some under-current, however indefinite of meaning. It is this latter, in especial, which imparts to a work of art so much of that richness (to borrow from colloquy a forcible term) which we are too fond of confounding with the ideal.”

To create this underlying suggestiveness he uses the first metaphoric expression “myheart” proposing a emblematic image of the raven that only reaches it's full meaning in the end of the poem representing the “Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance”.

“Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore!”

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting,

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming,

And the lamplight o’er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted — nevermore."

Of all the recommendations that he suposes inherent to his creative method, maybe the most important also the one he puts first in his essay:

“I prefer commencing with the consideration of an effect. Keeping originality always in view — for he is false to himself who ventures to dispense with so obvious and so easily attainable a source of interest — I say to myself, in the first place, “Of the innumerable effects, or impressions, of which the heart, the intellect, or (more generally) the soul is susceptible, what one shall I, on the present occasion, select?”

Old fashioned? Frigid? Maybe, but his importance to literature is undeaniable. With this honest exposure of his writing process, Edgar Allan Poe also make visible the daily effort behind the creative works we appreciate. And is there any problem in writing like this if the result if “The Raven”? So many years passed and there's still people making mistakes that he can teach how to avoid in “Philosophy of composition”.

Another interesting tip is to read interviews as a easier way to study and gather information. If you want to forget some of this cold-hearted calculation of the poem I recommend readingsome of what Lygia Fagundes Telles has to say about the mission of the writer.

Human Duties: Saramago's idea for a better world

“With the same vehemence as when we demanded our rights, let us demand responsibility over our duties.” - Saramago

Since the early days in school we learn: the “citizen” has rights and duties that, people say, are equal to everyone. However, when we study a bit more we discover a gradient that ranges from citizens full of duties and few rights to those that can do anything without being held responsible. A situation better summarized by the portuguese writer José Saramago:

"In this half-century, obviously governments have not morally done for human rights all that they should. The injustices multiply, the inequalities get worse, the ignorance grows, the misery expands." - Saramago

This speech, pronounced during the event in which he was laureated by the Nobel Prize in Literature, opened the dinner at December 10th in 1998, exactly fifty years after the signature of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Having so much attention during these moments, José Saramago seized the opportunity to proppose a counterpart to this essential document, he wanted the Declaration of Human Duties and Responsibilities.

Rough for the entrance of a gala event, he made clear that he didn't believed in social improvements coming from the governments due to many reasons, but mainly because the true rulers are the bigcompanies. And that if we wanted something, it would have to be achieved through the people, a fight in which the demands should emanate from a desire to assume the responsibilities that come with our rights.

“Let us common citizens therefore speak up. With the same vehemence as when we demanded our rights, let us demand responsibility over our duties. Perhaps the world could turn a little better.” -José Saramago

Saramago died in 2010 without seeing this project finished. But in June 2015 the foundation that carries his name, having the writer and translator Pillar del Río as president, gathered intelectualsand specialists from diferent areas to discuss the creation of the document proposed by the writer. The discussion aims to find the first directions for the creation of the document, even though the project still have to receive many contributions before reaching it's final formulaton:

“We need to change focus and perspectives, to breack with clichês in order to imagine a different world, só we can dare to think of a new utopia. To imagine a world where hunger, ignorance and the preventable deaths find no place, where there's no segregation due to race, religion, gender or economic reasons.” - José Narro Robles, UNAM's Dean.

At this first moment, Pillar del Río occupy a crucial position in the event and opens the debate without concerns with specificity while the objective remains clear. As a specialist in the works of the writer and also due to her personal life as his wife, she's the right person to point Saramago´s intentions, but knowing very well that if it grows it will be much bigger than the ambitions of only one person.

“We'll propose, diffuse and offer our means and possibilities and work as if everything depended on us, but being very conscious that it doesn't.” - Pillar del Río, president of the José Saramago Foundation.

The support or the critic about this attempt still depends on how this documents will be developed and it's content, for now we can only think and search answers to not so simple questions. To qustion the duties of every person, even their existence, can be a starting point to something that can become huge in the coming decades. When dealing with these complicated tasks it's important to remember the defense that Alain de Botton made about the professionals from the humanities and the solutions that can come from this field.

The interview as a tool for aspiring writers

The interview, at least from my utilitarian experience, became an important tool to find directives and discussions that could pass unnoticed by me.

If you, like me, try to write literature, then the lack of people with whom to discuss your efforts is probably a constant. I know that the internet exists to deal with this, but here I’m talking about a more helpful contact that also provides relevant content. Some time ago I discovered that the interviews given by other writers could be a midterm between talk and a more profound reading. There’s this certain informality of the dialogue, but also a lot of good content if you know where to find these interviews. All of this in a shorter format and without making you read an entire book about one theme at a time.

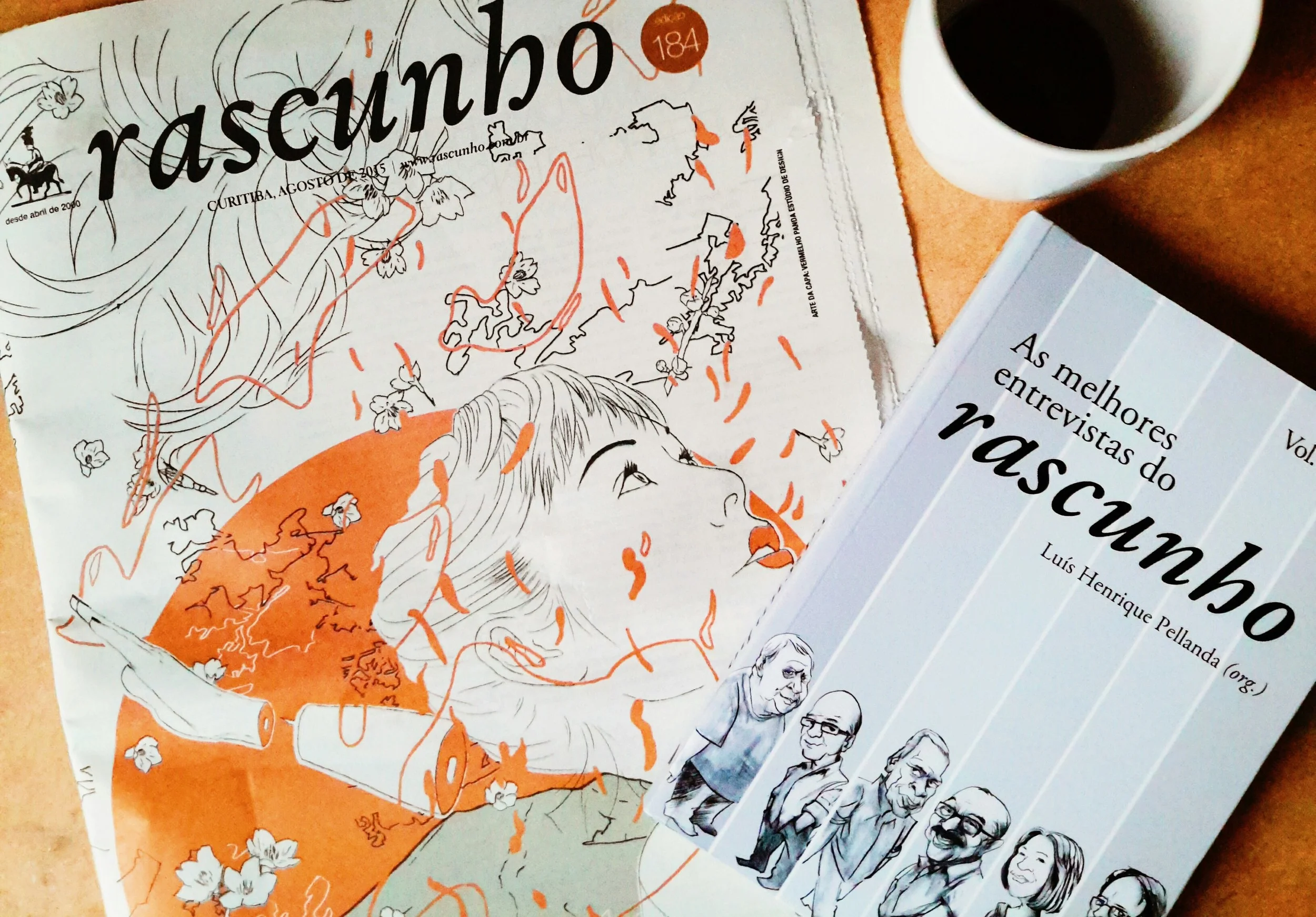

The usefulness that I see in interviews is the reason for why I share some interviews here, like the one of Lygia Fagundes Telles or Borges. Recently I won a copy from Rascunho’s book with the best interviews published by them. I’ve read this book so fast that know I can only go after the second volume.

However, both the preface signed by Luís Henrique Pellanda, the book organizer, and my experience reading interviews called my attention to an essential factor that sometimes can go unnoticed: the interviewer. It is not rare to see an interview ruined by lack of ability. In a good interview the knowledge and questions chosen by the interviewer should work together to allow the most interesting answers from the interviewed.

Roland Barthes already questioned the limits between the author and his works and this also applies to writer’s interviews. The content of the answer must be seen with some distance and that’s why I consider it a different contact than that allowed by books and essays, even when it’s an interview via e-mail. On interviews a lot of writers are hesitant to comment their own books or the avoid to give too many details about characters and creative processes. They make it clear: the interview’s communication shouldn’t complement the written work. Beyond that we must bear in mind the instantaneity of the interview and the difference between the written and the oral answer, even when transcribed.

The interview, at least from my utilitarian experience, became an important tool to find directives and discussions that could pass unnoticed by me. Clearly, the format, that is usually short, contribute to certain limitations in the approach deepness, although this aspect can be managed outside the interview genre. As a tool it’s a less impersonal reading to be arranged between studies and other harder readings. However, even with the utility I pointed here, I suspect that this is only a minor use of this kind of text.

Professionals from the Humanities matter, we just don’t know that

The humanities have some of the biggest clues out there about how to fix stuff. We’re very bad at a range of things that these art graduates could help us with.” – Alain de Botton

It's common to see graduations from the humanities, specially those related to arts like music, painting, literature and cinema, being taxed as useless or as graduations that “don’t pay well”. But if it’s true that they may not “pay well” it’s only because we can’t see the “utility” that these professional can have in our lives.

Zygmunt Bauman simplifies the contingencies of our world, through people’s instability and submission to an order that looks inevitable in our modern society. An order that demands flexibility from everyone, a readiness to fit in. However, this flexibility seems to demand too much from the humanities graduates because what we see is that in order to survive they need to abdicate their knowledge and interests.

The School of Life has what I consider one of the best Youtube channels. In their most recent video named “Why Arts Graduates Are Under-Employed”, Alain de Botton argues that the essence of the problem is in the lack of appropriate positions and employers, a problem of education and knowledge:

“But in truth the extraordinary rate of unemployment or misemployment of graduates in the humanities is a sign of something grievously wrong with modern societies. It’s evidence that we have no clue of what culture and art are really for and what problems it can solve.”

It’s not a problem if you’re not so sure about the benefits that culture and art can have to people in general, he tries to give some reasons as to why we are wasting these professionals when the best job we have for them is serving coffee:

“Good news is that the humanities actually do have a point to them. They’re a storehouse of vitally important knowledge about how to lead our lives. Novels teaches us about relationships. Works of art reframe our perspectives. Drama provides us with cathartic experiences. Philosophy teaches us to think, political science to plan and History is a catalogue of case-studies into any number of personal and political scenarios.

The humanities have some of the biggest clues out there about how to fix stuff. We’re very bad at a range of things that these art graduates could help us with.”

Ok, maybe not so many people think that the knowledfe from the humanities is useless. But our incapacity of harness these people to solve our common problems is, in it’s essence, proof of how much we need them:

“That there are so many arts graduates waiting tables isn’t a sign that they have been lazy and self-indulgent. It’s that we haven’t collectively woken up to what culture could really do for us and how useful and totally practical it could be.”

Full video below: