Professionals from the Humanities matter, we just don’t know that

The humanities have some of the biggest clues out there about how to fix stuff. We’re very bad at a range of things that these art graduates could help us with.” – Alain de Botton

It's common to see graduations from the humanities, specially those related to arts like music, painting, literature and cinema, being taxed as useless or as graduations that “don’t pay well”. But if it’s true that they may not “pay well” it’s only because we can’t see the “utility” that these professional can have in our lives.

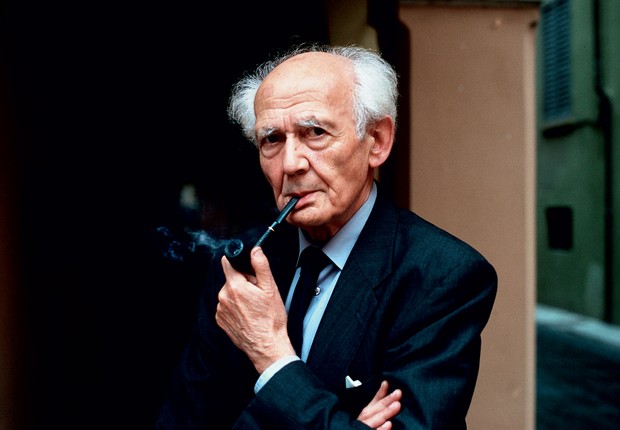

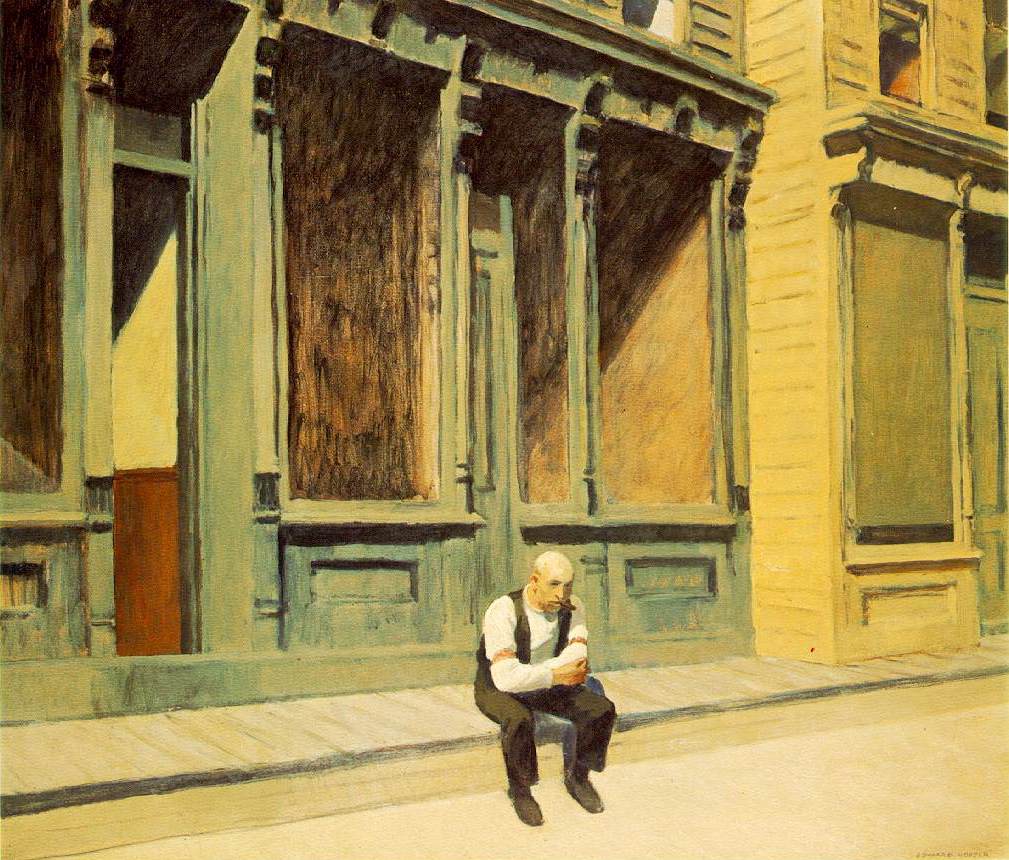

Zygmunt Bauman simplifies the contingencies of our world, through people’s instability and submission to an order that looks inevitable in our modern society. An order that demands flexibility from everyone, a readiness to fit in. However, this flexibility seems to demand too much from the humanities graduates because what we see is that in order to survive they need to abdicate their knowledge and interests.

The School of Life has what I consider one of the best Youtube channels. In their most recent video named “Why Arts Graduates Are Under-Employed”, Alain de Botton argues that the essence of the problem is in the lack of appropriate positions and employers, a problem of education and knowledge:

“But in truth the extraordinary rate of unemployment or misemployment of graduates in the humanities is a sign of something grievously wrong with modern societies. It’s evidence that we have no clue of what culture and art are really for and what problems it can solve.”

It’s not a problem if you’re not so sure about the benefits that culture and art can have to people in general, he tries to give some reasons as to why we are wasting these professionals when the best job we have for them is serving coffee:

“Good news is that the humanities actually do have a point to them. They’re a storehouse of vitally important knowledge about how to lead our lives. Novels teaches us about relationships. Works of art reframe our perspectives. Drama provides us with cathartic experiences. Philosophy teaches us to think, political science to plan and History is a catalogue of case-studies into any number of personal and political scenarios.

The humanities have some of the biggest clues out there about how to fix stuff. We’re very bad at a range of things that these art graduates could help us with.”

Ok, maybe not so many people think that the knowledfe from the humanities is useless. But our incapacity of harness these people to solve our common problems is, in it’s essence, proof of how much we need them:

“That there are so many arts graduates waiting tables isn’t a sign that they have been lazy and self-indulgent. It’s that we haven’t collectively woken up to what culture could really do for us and how useful and totally practical it could be.”

Full video below:

How to navigate Zygmunt Bauman’s liquid world

“If we wish them to become truly familiar, apparently familiar things need first to be made strange.” – Zygmunt Bauman

Your newsfeed has more stuff than you want or can read, daily. Your Whatsapp receive a lot of messages while you use Tinder to find a new date. We can travel anywhere and you just have to download something like Uber to have a driver waiting at your front door to take you to the airport while you do the check-in from your smartphone. All of this is reality to some people, but it’s a recent truth and it may not last. It’s this fluidity of the modern life and the meltdown of relations that Zygmunt Bauman study to give us some understanding of it.

Bauman is a polish sociologist who studies modern society, ranging from politics, through consumism and art. In his book “44 Letters from the Liquid Modern World” he compiles texts written from 2008 to 2009 for the magazine La Repubblica delle Donne. In these letters he introduces themes of this liquid world that seem familiar to us and try to help us understand them beyond our daily lives. His transition to the study of post-modernity is marked by the appearance of the term modern liquid world:

“From the ‘liquid modern’ world: that means from the world you and I, the writer of forthcoming letters and their possible/ probable/hoped for readers, share. The world I call ‘liquid’ because, like all liquids, it cannot stand still and keep its shape for long. Everything or almost everything in this world of ours keeps changing: fashions we follow and the objects of our attention (constantly shifting attention, today drawn away from things and events that attracted it yesterday, and to be drawn away tomorrow from things and events that excite us today), things we dream of and things we fear, things we desire and things we loathe, reasons to be hopeful and reasons to be apprehensive.”

The example I gave in the beginning is only the surface of the world as seen by Bauman, the changes occur in all areas and our anxieties tend to come even from the mere possibility of change:

“To cut a long story short: this world, our liquid modern world, keeps surprising us: what seems certain and proper today may well appear futile, fanciful or a regrettable mistake tomorrow. We suspect that this may happen, so we feel that – like the world that is our home – we, its residents, and intermittently its designers, actors, users and casualties, need to be constantly ready to change: we all need to be, as the currently fashionable word suggests, ‘flexible’. So we crave more information about what is going on and what is likely to happen. Fortunately, we now have what our parents could not even imagine: we have the internet and the world-wide web, we have ‘information highways’ connecting us promptly, ‘in real time’, to every nook and cranny of the planet, and all that inside these handy pocket-size mobile phones or iPods, within our reach day and night and moving wherever we do. Fortunately? Alas, perhaps not that fortunately after all, since the bane of insufficient information that made our parents suffer has been replaced by the yet more awesome bane of a flood of information which threatens to drown us and makes swimming or diving (as distinct from drifting or surfing) all but impossible. How to sift the news that counts and matters from the heaps of useless and irrelevant rubbish? How to derive meaningful messages from senseless noise? In the hubbub of contradictory opinions and suggestions we seem to lack a threshing machine that might help us separate the grains of truth and of the worthwhile from the chaff of lies, illusion, rubbish and waste . . .”

To understand or at least to have better tools to navigate this liquid world, Bauman seeks help from Walter Benjamin to propose two narrative forms. One of them is the narrative about bizarre actions and heroic deeds, those that are fabulous and have little to do with their listeners, the other one is the narrative of closer events, stories of the daily life that seem common, familiar. To Bauman even the more common and simpler stories can only be apparently familiar:

Zygmunt Bauman

“I said apparently familiar, since the impression of knowing such things thoroughly, inside out, and therefore expecting there to be nothing new to be learned from and about them, is also an illusion – in this case coming precisely from their being too close to the eye to see them clearly for what they are. Nothing escapes scrutiny so nimbly, resolutely and stubbornly as ‘things at hand’, things ‘always there’, ‘never changing’. They are, so to speak, ‘hiding in the light’ – the light of deceptive and misleading familiarity! Their ordinariness is a blind, discouraging all scrutiny. To make them into objects of interest and close examination they must first be cut off and torn away from that sense-blunting, cosy yet vicious cycle of routine quotidianity. They must first be set aside and kept at a distance before scanning them properly can become conceivable: the bluff of their alleged ‘ordinariness’ must be called at the start. And then the mysteries they hide, profuse and profound mysteries – those turning strange and puzzling once you start thinking about them – can be laid bare and explored.”

Bauman’s letters are a way to see while being inside the liquidity:

“Tales drawn from the most ordinary lives, but as a way to reveal and expose the extraordinariness we would otherwise overlook. If we wish them to become truly familiar, apparently familiar things need first to be made strange.”

When he defines the objective of his letters he also tell us what’s a possible objective to any intellectual endeavor, even if it demands a great effort to distinguish the signal from the noise. “44 Letters from the Liquid Modern World” is one of those rare books where the clarity don’t compromise the depth of the text.

Other recommended Reading that was already presented here is about how the world we create acts back on us and recreates us, the original article is written by Anne-Marie Willis.

Susan Sontag explores the primitive and the modern in photography

“Photographs are a way of imprisoning reality, understood as recalcitrant, inaccessible." - Susan Sontag

Susan Sontag was one of those restless minds that defy categories and limits. Born in 1933, she wrote about art, culture, politics and human rights with great resourcefulness. “The image-world” is an essay of her book “On photography”, which was originally published in 1977. Written during the 70's, these essays show a interconnected way of thinking the image, even considering their individuality.

In “The image-world”, Sontag uses her erudition to show the place of photography in the modern societies through comparisons with pre-industrial cultures or even pre-historic art. As we're going to see, photography and image, as proposed by her, are an extension as real as the original:

“Such images are indeed able to usurp reality because first of all a photograph is not only an image (as a painting is an image), an interpretation of the real; it is also a trace, something directly stenciled off the real, like a footprint or a death mask."

This quote is enough to show the challenges of proposing real that which is usually regarded to be only a representation. But she don't avoid the debate. By refering to Plato she defies a whole thinking tradition:

“But this venerable naïve realism is somewhat beside the point in the era of photographic images, for its blunt contrast between the image (“copy”) and the thing depicted (the “original”)—which Plato repeatedly illustrates with the example of a painting—does not fit a photograph in so simple a way. Neither does the contrast help in understanding image-making at its origins, when it was a practical, magical activity, a means of appropriating or gaining power over something. The further back we go in history, as E. H. Gombrich has observed, the less sharp is the distinction between images and real things; in primitive societies, the thing and its image were simply two different, that is, physically distinct, manifestations of the same energy or spirit. Hence, the supposed efficacy of images in propitiating and gaining control over powerful presences. Those powers, those presences were present in them.”

“What defines the originality of photography is that, at the very moment in the long, increasingly secular history of painting when secularism is entirely triumphant, it revives—in wholly secular terms—something like the primitive status of images. Our irrepressible feeling that the photographic process is something magical has a genuine basis. No one takes an easel painting to be in any sense co-substantial with its subject; it only represents or refers. But a photograph is not only like its subject, a homage to the subject. It is part of, an extension of that subject; and a potent means of acquiring it, of gaining control over it.”

Giving this condition of reality to the photo, she then argues that there's a true inversion in the way we see the real, a return to the primitive ways of dealing with the image:

“But the true modern primitivism is not to regard the image as a real thing; photographic images are hardly that real. Instead, reality has come to seem more and more like what we are shown by cameras. It is common now for people to insist about their experience of a violent event in which they were caught up—a plane crash, a shoot-out, a terrorist bombing—that “it seemed like a movie.” This is said, other descriptions seeming insufficient, in order to explain how real it was."

“It is as if photographers, responding to an increasingly depleted sense of reality, were looking for a transfusion—traveling to new experiences, refreshing the old ones.”

“The urge to have new experiences is translated into the urge to take photographs: experience seeking a crisis-proof form.“

Being real, the mobility of the image can be a relief to those who can't experience that content, no matter if the reason is due to time or because of other kinds of constraints:

“As the taking of photographs seems almost obligatory to those who travel about, the passionate collecting of them has special appeal for those confined—either by choice, incapacity, or coercion—to indoor space. Photograph collections can be used to make a substitute world, keyed to exalting or consoling or tantalizing images.”

“For stay-at-homes, prisoners, and the self-imprisoned, to live among the photographs of glamorous strangers is a sentimental response to isolation and an insolent challenge to it.”

“Photographs are a way of imprisoning reality, understood as recalcitrant, inaccessible; of making it stand still. Or they enlarge a reality that is felt to be shrunk, hollowed out, perishable, remote. One can’t possess reality, one can possess (and be possessed by) images—as, according to Proust, most ambitious of voluntary prisoners, one can’t possess the present but one can possess the past.”

While the photo grants us the chance to keep contact with what's past and some of it's substance, there's also the need to deal with the transference of value that can happen between the “things” and their “images”, something that concerned Plato, even though he didn't saw this phenomenon as a competition between realities, but as the destruction of the only possible reality. Sontag don't accept this argument:

“The attempts by photographers to bolster up a depleted sense of reality contribute to the depletion. Our oppressive sense of the transience of everything is more acute since cameras gave us the means to “fix” the fleeting moment.”

“The powers of photography have in effect de-Platonized our understanding of reality, making it less and less plausible to reflect upon our experience according to the distinction between images and things, between copies and originals. It suited Plato’s derogatory attitude toward images to liken them to shadows—transitory, minimally informative, immaterial, impotent co-presences of the real things which cast them. But the force of photographic images comes from their being material realities in their own right, richly informative deposits left in the wake of whatever emitted them, potent means for turning the tables on reality—for turning it into a shadow. Images are more real than anyone could have supposed.”

“On photography” is an essential reading to thing the image in our society. The internet and social networks may have added another anxieties and needs to these already proposed by Susan Sontag, however, it's inevitable to read her writings in order to reach something more in this field.

If you want to understand better Plato's hesitation in regarding copies and imitations you can find here the Reading Notes about Plato's idea of expelling the poets from the ideial city. And to have an ideia about how it's possible to change the world through photos and videos read article about Ontological Design as seen by Anne-Marie Willis.

Solitude, pacifism and religious feeling, as seen by Albert Einstein.

“The fairest thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true art and true science.” - Albert Einstein

Universally known by his discoveries, today Albert Einstein is an icon both of popular and scientific cultures. Aware that his singular position as academic granted him influence beyond Physics, Einstein defended some of his political worries and humanistic aspirations. In his letters and essays we find a person worried about the future of humanity and in conflict with problems that also affected him personally. The militarism, the fanatic nationalism and the anti-semitism are always targets of his critics.

Originally published in 1931, his essay “The world as I see it” shows how, even before the rise of the Nazi regime and his unconfortable relation with the nuclear race, he already had a well formed political and humanist line of thought. Conscious of his limitations and sober despite what the world saw in him, Einstein writes:

“Each of us is here for a brief sojourn; for what purpose he knows not, though he sometimes thinks he feels it.”

“Schopenhauer’s saying, that “a man can do as he will, but no will as he will,” has been na inspiration to me since my youth up, and a continual consolation and unfailing well-spring of patience in the face of the hardships of life, my own and others’.”

By praising empathy not only as a objective of his life, but also as a something to be pursued, Einstein show his worry in fighting against the brutality of the world:

“My passionate sense of social justice and social responsibility has always contrasted oddly with my pronounced freedom from the need for direct contact with other human beings and human communities. I gang my won gait and have never belonged to my country, my home, my friends, or even my immediate family, with my whole heart; in the face of all these ties I have never lost an obstinate sense of detachment, of the need for solitude – a feeling which increases with the years.”

At the same time his efforts to connect with other people demanded great effort he also noticed that the incomprehension and the struggle was reciprocal. To him, this reticence in relation to how people saw him was extended to his own ideas, even less understood in his time than today:

“It is an irony of fate that I myself have been the recipient of excessive admiration and respect from my fellows through no fault, and no merit, of my own. The cause of this may well be the desire, unattainable for many, to understand the one or two ideas to which I have with my feeble powers attained through ceaseless struggle.”

Militant pacifist, the militarism is the only subject that makes him go beoynd the critic, showing even contempt for the armed forces. These and other of his more progressive reivindications granted him the label of left militant by the US government, reason for the serious precautions to keep Einstein out of the Manhattan Project:

"This topic brings me to that worst outcrop of the herd nature, the military system, which I abhor.

[…]

This plague-spot of civilization ought to be abolished with all possible speed. Heroism by order, senseless violence, and all the pestilent nonsense that goes by the name of patriotism – how I hate them!"

Despite being upset about the distance between him and other people and his insatisfaction with some of the pillars of the society, he's still optimistic enough to say:

“And yet so high, in spite of everything, is my opinion of the human race that I believe this bogey would have disappeared long ago, had the sound sense of the nations not been systematically corrupted by commercial and political interests acting through schools and the Press.”

The organized religion and the bling theism don't go unscathed under his critic eye. He put himself closer to common poeple when talking about his fears and doubts and admiting his religious feeling about the inescrutable nature, however, his distance is clear when this feeling leads to conceptions incompatible with his ideas:

“The fairest thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true art and true science.

[…]

A knowledge of the existence of something we cannot penetrate, of the manifestations of the profoundest reason and the most radiant beauty, which are only accessible to our reason in their most elementary forms – it is this knowledge and this emotion that constitute the truly religious attitude; in this sense, and in this alone, I am a deeply religious man. I cannot conceive of a God who rewards and punishes his creatures, or has a will of the type of which we are conscious in ourselves. An individual who should survive his physical death is also beyond my comprehension, nor do I wish it otherwise; such notions are for the fears or absurd egoism of feeble souls. Enough for me the mystery of the eternity of life, and the inkling of the marvelous structure of reality, together with the single-hearted endeavor to comprehend a portion, be it never so tiny, of the reason that manifests itself in nature.”

Short and rich, this essay is important because it shows us how things can walk slowly, since being pacifist, defend the ones who need and criticize religious absurdities are lines of thought still regarded as progressist. But from Einstein we can learn that any possibility, be it big like the ones he had or small like the ones from our daily lives, have to be used to replicate the ideas we need.

Einstein wasn't the only one to point the brutality of his time, Franciso de Goya also witnessed how the hateful military institutions are one of the greatest obstacles to civilization. Thinking about culture it's worth to take a look at Joyce's view of the cultural formation of the modern man.