5 quotes: The Devil's Dictionary by Ambrose Bierce

The Devil’s Dictionary by Ambrose Bierce exudes sarcasm, humour, misanthropy, irony and also a sharp point of view, even if it’s disguised by it’s funny and acid style. The extended version was published in 1911 being to this day a book that explains more about humanity than the words it compiles.

1

“CHRISTIAN, n.

One who believes that the New Testament is a divinely inspired book admirably suited to the spiritual needs of his neighbor. One who follows the teachings of Christ in so far as they are not inconsistent with a life of sin.”

2

“ELECTOR, n.

One who enjoys the sacred privilege of voting for the man of another man’s choice.”

3

“PHILISTINE, n.

One whose mind is the creature of its environment, following the fashion in thought, feeling and sentiment. He is sometimes learned, frequently prosperous, commonly clean and always solemn.”

4

“HOMŒOPATHIST, n.

The humorist of the medical profession.”

5

“OCCIDENT, n.

The part of the world lying west (or east) of the Orient. It is largely inhabited by Christians, a powerful subtribe of the Hypocrites, whose principal industries are murder and cheating, which they are pleased to call “war” and “commerce.” These, also, are the principal industries of the Orient.”

Reference: The Devil's Dictionary

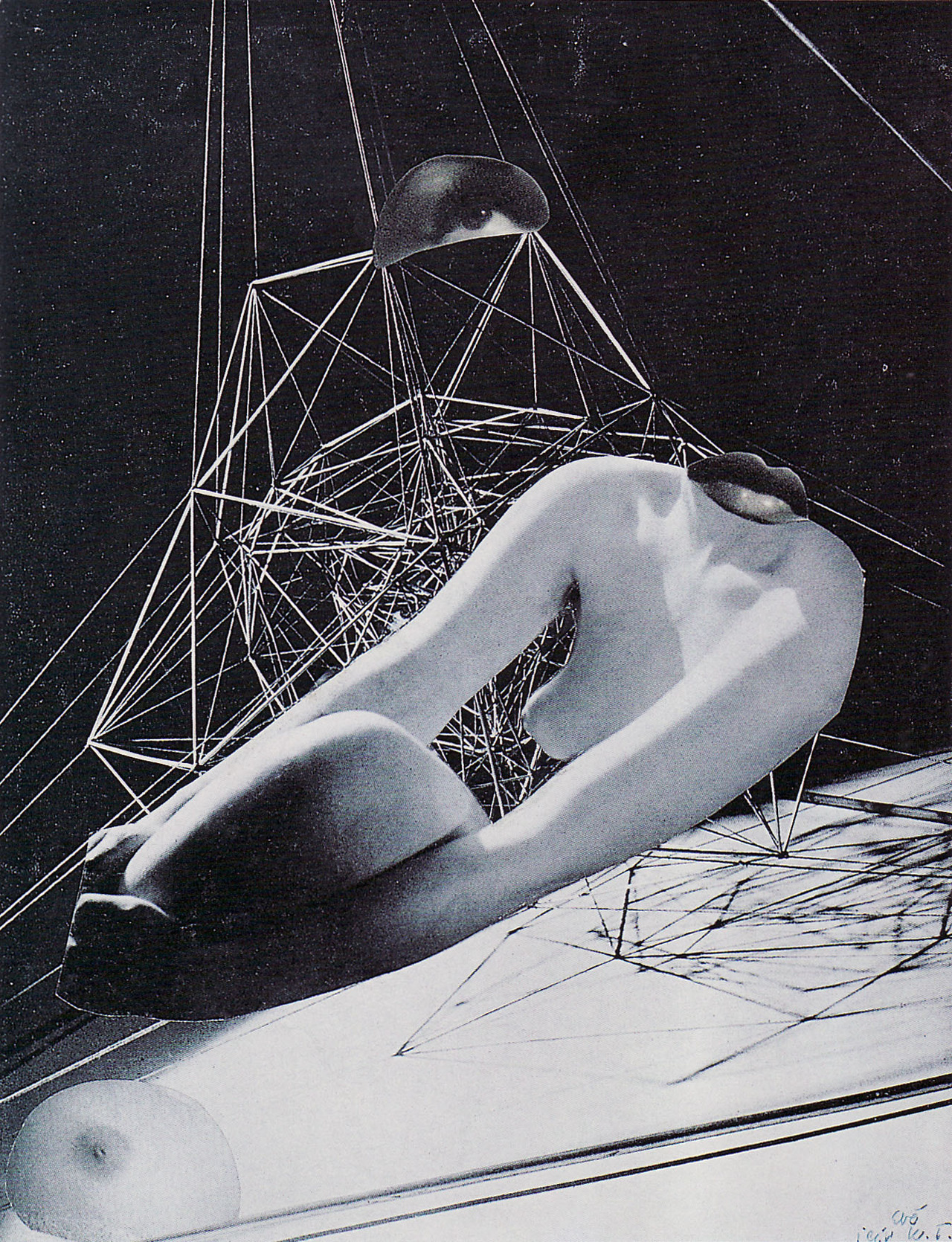

5 quotes to make you read: Adventures in immediate irreality by Max Blecher

Shortly before dying at 28, Max Blecher published “Adventures in immediate irreality” a book whose labels range from surrealist to hyperrealist. If the definition is unclear it’s because the book also deals with foggy aspect of the being and the reality with such a sharp eye that justifies all comparisons between him and names like Kafka, Proust and Schulz.

1

“When I stare at a fixed point on the wall for a long time, it sometimes happens that I no longer know who I am or where I am. Then I feel my absence of identity from a distance as if I had become, for a moment, a complete stranger. With equal force, this abstract character and my real self struggle to win my conviction.”

2

“Ordinary words are not valid at certain spiritual depths. I’m trying to define my spells exactly but only find images. The magic word that could express them would have to borrow something from the essence of other sensibilities in life, distilling itself from them like a new scent from a masterly concoction of perfumes.

For the word to exist, it should contain something of the stupefaction that grips me when I see a person in reality and then follow their gestures in a mirror, plus something of the disequilibrium of falling in dreams with the whistling fear that runs down the spine in an unforgettable instant; or something of the fog and transparency inhabited by bizarre scenes in crystal balls.”

3

““How splendid, how sublime it is to be crazy!” I would say to myself, and observe with unimaginable regret how powerful stupid and familiar habits were, and that crushing rational upbringing separated me from the extreme freedom of a life of madness.”

4

“My distrust in the art of the painter gave way to a newborn boundless admiration.

In it I felt the distress of not having observed the essential quality of the picture earlier and at the same time a growing uncertainty of all that I saw: since I had contemplated the drawings for so many years without discovering the material they were composed of, couldn’t it be that through a similar myopia the meaning of all the things around me escaped me, though it was inscribed in them, maybe as clearly as the letters making up the pictures?”

5

““Your life was thus and not otherwise” says my memory, and in this pronouncement lies the immense nostalgia of the world, enclosed in its hermetic lights and colors from which no life is permitted to extract anything other than the aspect of an exact banality.

In it lies the melancholy of being unique and limited, in a unique and pathetically arid world.”

Reference: Max Blecher. Adventures in immediate unreality. Translation: Jeanie Han.

5 quotes to make you read: The invention of Morel by Bioy Casares

It was the seventh book published by Bioy Casares, but for him only after “The invention of Morel” his literary career started. In this book a fugitive hide himself in a deserted island where there’s an old museum until the day when the island receive unexpected guests. It’s from this simple premise that Casares create constant distortions between sanity and folly, real a imaginary.

1

“I examined the shelves in vain, hoping to find some books that would be useful for a research project I began before the trial. (I believe we lose immortality because we have not conquered our opposition to death; we keep insisting on the primary, rudimentary idea: that the whole body should be kept alive. We should seek to preserve only the part that has to do with consciousness.)”

2

“Perhaps my “no hope” therapy is a little ridiculous; never hope, to avoid disappointment; consider myself dead, to keep from dying. Suddenly I see this feeling as a frightening, disconcerting apathy. I must overcome it.”

3

“I am in a bad state of mind. It seems that for a long time I have known that everything I do is wrong, and yet I have kept on the same way, stupidly, obstinately. I might have acted this way in a dream, or if I were insane— When I slept this afternoon, I had this dream, like a symbolic and premature commentary on my life: as I was playing a game of croquet, I learned that my part in the game was killing a man. Then, suddenly, I knew I was that man.”

4

“The habits of our lives make us presume that things will happen in a certain foreseeable way, that there will be a vague coherence in the world. Now reality appears to be changed, unreal. When a man awakens, or dies, he is slow to free himself from the terrors of the dream, from the worries and manias of life.”

5

“A recluse can make machines or invest his visions with reality only imperfectly, by writing about them or depicting them to others who are more fortunate than he.”

Reference: The Invention of Morel. Adolfo Bioy Casares. Translation: Ruth L. C. Simms. New York Review of books.

5 quotes to make you read: Notes from the underground by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Through a nameless, lonely and unhappy narrator, Dostoyevsky goes from the monologue to the narrative in a short but powerful book in which, in the end, nothing stays unharmed during the life of the underground man.

1

“In short, one may say anything about the history of the world—anything that might enter the most disordered imagination. The only thing one can’t say is that it’s rational. The very word sticks in one’s throat.”

2

“Another circumstance, too, worried me in those days: that there was no one like me and I was unlike anyone else. ‘I am alone and they are EVERYONE,’ I thought—and pondered.

From that it is evident that I was still a youngster.”

3

“And how few, how few words, I thought, in passing, were needed; how little of the idyllic (and affectedly, bookishly, artificially idyllic too) had sufficed to turn a whole human life at once according to my will. That’s virginity, to be sure! Freshness of soil!”

4

“But at this point a strange thing happened. I was so accustomed to think and imagine everything from books, and to picture everything in the world to myself just as I had made it up in my dreams beforehand, that I could not all at once take in this strange circumstance. What happened was this: Liza, insulted and crushed by me, understood a great deal more than I imagined. She understood from all this what a woman understands first of all, if she feels genuine love, that is, that I was myself unhappy.”

5

“Leave us alone without books and we shall be lost and in confusion at once. We shall not know what to join on to, what to cling to, what to love and what to hate, what to respect and what to despise. We are oppressed at being men—men with a real individual body and blood, we are ashamed of it, we think it a disgrace and try to contrive to be some sort of impossible generalised man.”